Why the Ninth Inning Is So Tough

Although some front offices and analytics departments insist otherwise, the final three outs of a game are often the hardest to get. “There’s a big difference between the 23rd out and the 27th out,” retired pitcher Bruce Hurst said in the episode “#8: 1986 ALCS Game Five” of MLB Network’s MLB’s 20 Greatest Games (2010). Asking around amongst present-day players and coaches, they seem to agree. Arizona Diamondbacks left-hander Madison Bumgarner — a starter who has also pitched in relief during the postseason — broke it down even further. When closing out a complete game as a starter, he said the final three outs — at least for him — were the easiest. But as a reliever, he said, they were the hardest. This raises the question of why. Why is the ninth inning so tough? And why are the last three outs of a game the toughest to get?

San Francisco Giants manager Gabe Kapler agreed outs 25, 26, and 27 were the hardest three outs to get, but said the reasons are “very individual.” He stated, “If you ask ten different guys…you’ll probably get ten different answers.” He was close. During the Diamondbacks–Giants the last weekend in September, this reporter asked nine different guys and got about a dozen different answers.

(Note: Everything we say about the ninth inning being tough also applies in extra innings.)

Opponent Operates Differently

One explanation for why the ninth inning is so tough to close out centers around opponent behavior. The inning simply plays out differently. Teams pull out all stops. If they sat one of their studs, there is a good chance he’ll pinch-hit in the ninth. Consequently, instead of facing a number-eight or number-nine hitter who’s batting close to .200 with two home runs, the pitcher might face the league batting champion or a top-five slugger.

But there’s more. In a spring training interview, Diamondbacks reliever Ian Kennedy said the trailing team in the ninth inning of a close game has “more sense of urgency” offensively. “The seventh, eighth, and ninth hitters become better because they want to turn a lineup over. That way the top of the lineup can get in there,” he said. Diamondbacks reliever Joe Mantiply added, “At that point, everybody knows that’s the end of the game. Everybody’s a little more focused and emptying the tank of what they have (left) to try to win the game.” Diamondbacks reliever Mark Melancon —fourth on the active list in career saves — agreed with Mantiply. “Your back is up against the wall if you’re down. You’re trying to score runs, and there’s an added pressure on (the pitcher’s) side.”

Mantiply brought up another factor. When entering late in the game, “you get loose and warm, but the guys you’re facing, that’s usually their third or fourth at-bats of the day. They’re pretty locked in. You’ve got to be able to match their intensity. The hitters are a little more comfortable in what they’re doing that day. Trying to match that is pretty tough.”

Amplified Mistakes

Another tough aspect of the ninth inning is the tiny margin for error. “One pitch can change the game,” Melancon said. “Every little thing you do is critical — every pitch, every decision. If there happens to be an error, that blows up to be a lot more crucial.” Diamondbacks manager Torey Lovullo added, “If your closer is in the game, you know it’s going to be a close game. Anybody that blinks is probably gonna get sucker-punched in the face, and both teams know that.”

Diamondbacks pitching coach Brent Strom went into more detail. “As a starter, when you give up runs early, you don’t feel as stressed. You still have time for your offense to come back, even though a run given up in the second inning impacts the score as much as it does in the ninth.”

Examples

Embed from Getty Imageswindow.gie=window.gie||function(c){(gie.q=gie.q||[]).push(c)};gie(function(){gie.widgets.load({id:’2R-lbFTSSyBr4Z-3_9vIyg’,sig:’bn5KgWIXZNtD17MI8buX95ztD4e1jzFBmtz0TIAl3FU=’,w:’594px’,h:’447px’,items:’130661279′,caption: true ,tld:’com’,is360: false })});

Baseball has dozens of examples to back these statements up. Take Game Six of the 2011 World Series. If Mark Lowe had thrown the mistake pitch to David Freese in the seventh, the Rangers still would have had time to come back. Instead, it came in the bottom of the 11th of a tie game, and Freese became a postseason legend. Tony Fernandez made a fielding error for the Cleveland Indians in Game Seven of the 1997 World Series. If it had happened in, say, the sixth, it would have been costly but not fatal. But it happened in the bottom of the 11th. Instead of turning an inning-ending double play, it put the eventual World Series-winning run on base.

Monday night against the Milwaukee Brewers, Mantiply pitched the bottom of the ninth. With runners on second and third, two out, and the Diamondbacks holding a 4–2 lead, catcher Victor Caratini hit a grounder to first. This should have been the final out of the game. However, Christian Walker — far and away the best defensive first baseman in the majors — made a rare error, bringing in the tying runs. Later, Reyes Moronta failed to record an out in the bottom of the 10th, giving the Brewers a 6–5 victory.

Psychological Factors of the Ninth Inning

Several other factors mentioned by the interviewees revolved around the psychological aspect of pitching the ninth. A big part of finishing off an opponent comes from mentality. Retired major league pitcher John D’Acquisto, who succeeded Rollie Fingers as the closer with the San Diego Padres, said about opponents, “They can smell fear.” Giants pitching coach Andrew Bailey, himself a retired closer, agreed. “Fear of failure is a big thing,” he said. “As soon as that slips in your mind, the inning’s over.”

If a closer gets behind in the count, he can’t be afraid of what Bailey calls the “confidence ball” — a pitch on 2–0 that must be a strike. The attitude must be “here it is, hit it” — daring the batter to hit a tough pitch in the zone. Bailey said the pitcher must also embrace “the pressure” and have “the fortitude to persevere when a runner gets on base to not let him score. Leave it out there, day in and day out.”

Consequently, a certain mindset is required to pitch the ninth. D’Acquisto calls it the “Gunslinger Mentality.” Closers must think they’re the best pitcher out there. They require full confidence and must be prepared for the toughest opponent every time. Furthermore, they cannot show weakness. “Fish or cut bait,” he said. “You have to go with your best. If your opponent beats you, make them beat you with your best.” He smiled as he added, “But also win with your best.”

Not Everyone Can Do It

As Melancon mentioned, “If the home team is down in the ninth, the fans get more into the game and change the atmosphere.” For that and the other reasons we’ve discussed, the ninth inning is not an inning everyone can pitch successfully. And this is despite the fact that, as Bailey pointed out, “high leverage can really come in any inning. The game can be won in the first, second, third, fourth, or fifth. There are guys that can come in mid-inning behind the starter and get outs. And there are guys who need clean innings (an inning with no inherited runners). There are guys who can and can’t throw the ninth.”

“There’s just something about trying to close out a game,” said Strom, who never had to close a game unless he was trying to finish off a complete game. “It’s a different animal…. I asked Nolan Ryan one time who was the greatest closer he ever played with, and he said himself…. The most difficult inning for a starter is usually the first, and the most difficult batter for a reliever is usually the first, until they get their feet on the ground.”

As we’ve seen, there is strong agreement that the last three outs of the game are the toughest outs for relievers to get. But we’ve also seen that no one definitively knows why the ninth inning is so tough, although several theories abound. “If you solve it, let me know,” Bailey grinned. “There is something innate about those outs — specifically 25, 26, and 27 — that is just different. I don’t really have a good answer. But I think that’s what’s so fascinating, and it’s why we love the games. Those little things that you just can’t quantify.”

Video of Hurst’s Quote:

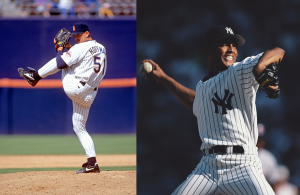

Main Photo:

The main photo is a composite of the following two images:

Embed from Getty Imageswindow.gie=window.gie||function(c){(gie.q=gie.q||[]).push(c)};gie(function(){gie.widgets.load({id:’txptc6cDQCR16IZTsI2N1w’,sig:’3iskyXci93t6Wf0-w4tG8WDg_EMRo4GCeMlNS9C4r2Q=’,w:’416px’,h:’594px’,items:’632699458′,caption: true ,tld:’com’,is360: false })});

Embed from Getty Imageswindow.gie=window.gie||function(c){(gie.q=gie.q||[]).push(c)};gie(function(){gie.widgets.load({id:’jyZYt32VQdF4PHAWNBYPaw’,sig:’092irmGv8OjxgCSsFtJkFOY-QpR08F6M77sSstXwYl0=’,w:’499px’,h:’594px’,items:’1011208098′,caption: true ,tld:’com’,is360: false })});

Players/managers mentioned:

Bruce Hurst, Madison Bumgarner, Gabe Kapler, Ian Kennedy, Joe Mantiply, Mark Melancon, Torey Lovullo, Brent Strom, Mark Lowe, David Freese, Tony Fernandez, Victor Caratini, Christian Walker, Reyes Moronta, John D’Acquisto, Rollie Fingers, Andrew Bailey, Nolan Ryan

The post Pitching the Ninth Inning: Why the Last Three Outs Are the Toughest to Get appeared first on Last Word On Baseball.